“The casualties are not only those who are dead.”

The lines from the poem ‘Casualties’ by celebrated author and poet JP Clark resonated in my mind as I read this beautifully written memoir ‘Floating In A Most Peculiar Way’ by Boston University Professor, Louis Chude-Sokei.

Keen readers of Biafran history or at least the throve of literary works that have been based on the unfortunate three-year war between 1967 and 1970, would have encountered the name of Lt Col Chude Louis Sokei, Sandhurst trained officer who became the Chief of Biafran Air Force and was killed by mortal fire by advancing federal troops around Ogidi in March of 1968.

He was married to a Jamaican woman and had a son not quite two at the time of his passing. Not many may have thought to wonder ‘so what became of them?’ This memoir serves a frank, rich and profound peep into their story since then.

“Throughout my childhood, my mother told me that we were from a country that had disappeared or been ‘killed’…. Sometimes, our country has been ‘starved to death.’” Chude-Sokei writes in the prologue of the book.

For readers who have not previously encountered stories of what has been described as ‘Africa’s first televised war’ or those photos of emaciated babies with swollen heads and stomachs that still grace the pages of global charity, the idea of coming from a country that no longer exists may sound rather strange or even remarkable. But that is the author’s reality. His mother, with the author strapped to her back had made it out on one of the last flights out of Biafra, to a refugee camp in Gabon from where she returned to her home country, Jamaica.

In the first few chapters, Chude-Sokei writes about his early childhood, living in Montego Bay, in a home for children left behind by mothers who had gone off in search of greener pastures in the likes of Canada, America or England and waiting to be taken themselves.

His mother had moved to America to work.

The young Chude-Sokei had little or no recollection of where he was from. “All I had with me when I arrived in Jamaica,” he writes, “was a song, not an Igbo song but a Western one played on the radio about floating in space and choosing never to come down. It was a song about someone named Major Tom, and it eventually became my only memory of my origins in Africa.”

But the visit of strange men from Africa, ex-soldiers of the ward who accorded him so much reverence and referred to him as ‘the first son of the first son’ will provide the first clear indications of his origins and the fact that he was born into something big.

‘Floating In A Most Peculiar Way’ can be described as a coming of age story. But it is a lot more. It is about displacement, race, self-discovery and acceptance of self. Chude-Sokei not only seeks answers to questions about his father, the war and about his homeland, but also about the colour of his skin and what it means to be black or African, in America.

First arriving in Washington, DC, before he and his mother relocated to Los Angeles, Chude-Sokei is confronted by a new set of complexities. He writes about the racism he faced from both whites and Black Americans which is a familiar lived experience of many African Diaspora. With very fine storytelling, he narrates how he walked the fine lines of race on the streets of Inglewood, Los Angeles, in the wake of gangsta rap and the LA riots, balancing accusation of ‘acting white’ because he liked to read books and his long-held ambitions of being African American.

The tension between Black Americans and African immigrants come through in the book. It is interesting to note that while the commentary at the time Chude-Sokei was growing up was that “Africans were backward and spent all their time killing one another, like in Uganda and Biafra, and were an embarrassment to real black people.”, today that conversation has morphed into some kind of xenophobia with African immigrants being blamed by the Black Americans for their inability to be successful.

Just recently this was a trending topic on twitter following a Twitter Space moderated notably by one Tariq Nasheed which amplified the notion that African Americans wanted Africans to stop coming to their country. It was the submission of Tariq and his co-hosts that the African Diaspora in America were taking away jobs and other opportunities that ought to come to the ‘foundational’ black Americans and making it more difficult for them to get the reparation they deserve.

Chude-Sokei will finally come home, a visit that was to help him fit the missing pieces of the puzzles of his life but which in some way raised new questions or added additional pressures as he came under a barrage of new information, expectations including the discovery of the full version (and meaning) of his Igbo name. He describes his meeting with his godfather, the erstwhile leader of the nation that was no more, then under house arrest in Lagos.

Ojukwu and his father had been together at Sandhurst. There, over dinner and bottles of beer he learnt a bit about the personality of his father and how once he met his mother, he knew she was the one he should (not would) marry. “He was an Onitsha man” his godfather said of his father “but Onitsha people have always been different…But he, was different among the different….Everything he did was accepted as traditional, even marrying your mother”

Cancer will later take his mother, but not before she extracted a promise from him to bury her in Nigeria, next to her husband in the precinct of the house he had built for her, before things fell apart. A promise, he kept much to the delight of this reader.

There is no doubt that Chude-Sokei writes about a difficult life trying to navigate complex issues which he had no hand in making. Indeed, like JP Clark’s poem, he is a casualty of that war which left him a Biafran, Nigerian, Jamaican and American without ever fully being any of those. In some way, it is a sad tale. But he does tell it with grace, devoid of bitterness and with a frankness that elates, highlighting in his prose, his own vulnerabilities and imperfections.

‘Floating In A Most Peculiar Way’ is a great read and a worthy addition to both the catalogue of books about the Biafran war and the lived experiences of African immigrants in America. And without perhaps being the intention of the author, it contributes to the ongoing debate both in the academia as is in pop culture, on what it means to be Black, today.

Sylva Nze Ifedigbo, creative writer and social commentator is the author of Believers and Hustlers. He is available on social media at @nzesylva.

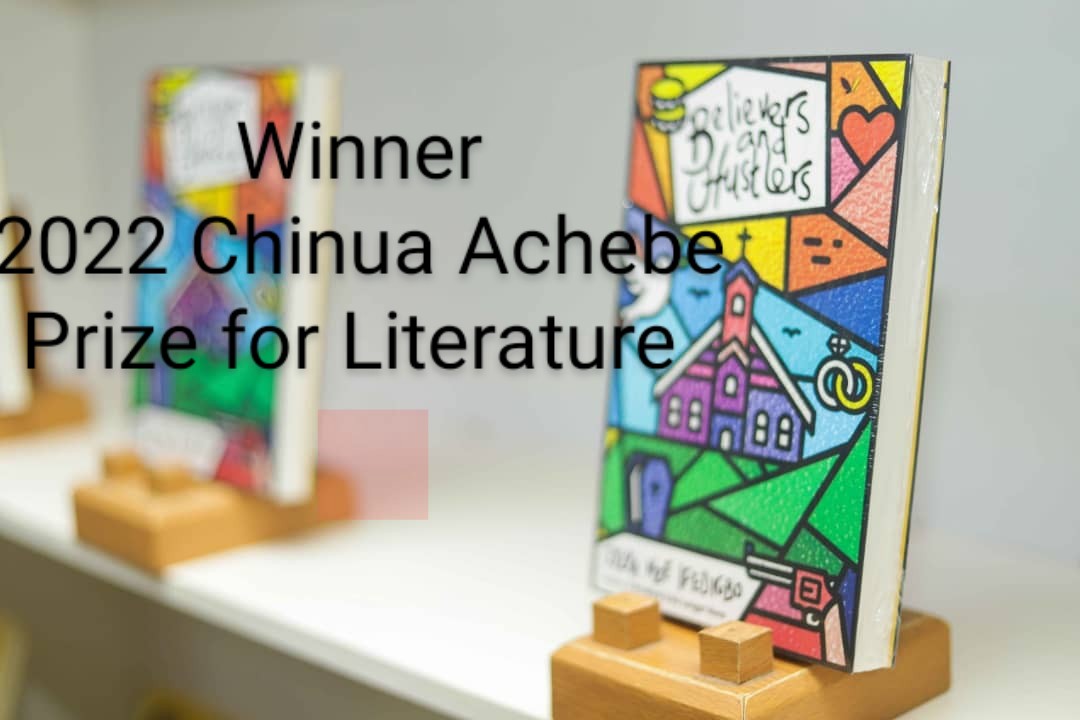

On Saturday 29 October 2022, the grand award dinner of the 41st Convention of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), I was named winner of the 2022 Chinua Achebe Prize for Literature for my book, Believers And Hustlers.

On Saturday 29 October 2022, the grand award dinner of the 41st Convention of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), I was named winner of the 2022 Chinua Achebe Prize for Literature for my book, Believers And Hustlers.

Afi Tekple and her mother are made homeless and driven to poverty following the untimely death of her civil servant father. Denied of any inheritance by the greedy and opportunistic Uncle Pious, they are rescued by Aunty Faustina, the matriarch of the Ganyo family who puts them up and gives Afi’s mother a job at her flour distribution depot.

Afi Tekple and her mother are made homeless and driven to poverty following the untimely death of her civil servant father. Denied of any inheritance by the greedy and opportunistic Uncle Pious, they are rescued by Aunty Faustina, the matriarch of the Ganyo family who puts them up and gives Afi’s mother a job at her flour distribution depot.